- The riches of Vienna’s museums are almost overwhelming. Developed from the art collections of the House of Habsburg, the Kunsthistorisches Museum boasts one of the most important collections of great master paintings in the world. Masterpieces by Vermeer, Rembrandt, Velazquez, Titian, and Rubens rub shoulders with Van Dyck, Durer and Cranach while its holding of a dozen pictures by Pieter Bruegel the Elder is unrivalled. And that is only the tip of the iceberg. Antiquities, jewelley, gold and silver work, rare textiles and tapestries, arms and armour furnish the marbled halls in exhausting profusion.

Given this high culture and a wealthy and conservative bourgeois class to appreciate it, the Austrian capital was an unlikely place to embrace a ground breaking exhibition devoted to the art of unknown, untrained and undisciplined artists operating on the margins of society, often referred to as ‘Outsiders.’ But just last year the Kunstforum of the Bank Austria did exactly that, hosting a show, Flying High, devoted to an art form that 100 years ago would have outraged the good burghers of the city but instead showed how such art has become big business.

Also known as Art Brut – or Raw Art – it consists (in the main) of work by psychiatric patients, psychics, loners, naifs, folk artists and Sunday painters: in general artists working outside the mainstream, often in isolation, an ill defined collective of men and women, many anonymous, whose products have begun to grab the attention of collectors and dealers. Sometimes their works only came to light after their deaths.

Outsider art often illustrates extreme mental states, unconventional ideas, or elaborate fantasy worlds in which disturbing creatures of the subconscious mind are unleashed. By its very nature it has been a difficult topic but that is certainly all changing. The historical barriers between Outsider art and “high” art have rapidly been breaking down in the past two decades and the very ‘democratic’ nature of outsider art has made it popular with collectors. Indeed, a form of market mania is a manifestation of this. There are two magazines – Raw Vision and Outsider Art – devoted generally to the subject and since 1993 international Outsider art fairs have promulgated the genre and numerous documentaries have been made.

Jean Dubuffet, who coined the term Art Brut in 1945 for art produced outside the mainstream – his own included – was one of the first to systematically collect such art. Many of the works he amassed came from psychiatric hospitals.

One of the most widely known names in this field that of Richard Dadd (1817–1886), noted for his beautiful depictions of fairies and supernatural beings in woodland settings. The works were created while Dadd was a patient in the Bethlem hospital (once known as Bedlam) where he was held for 20 years and cared for by enlightened doctors, one of whom, Alexander Morison, also collected his work.

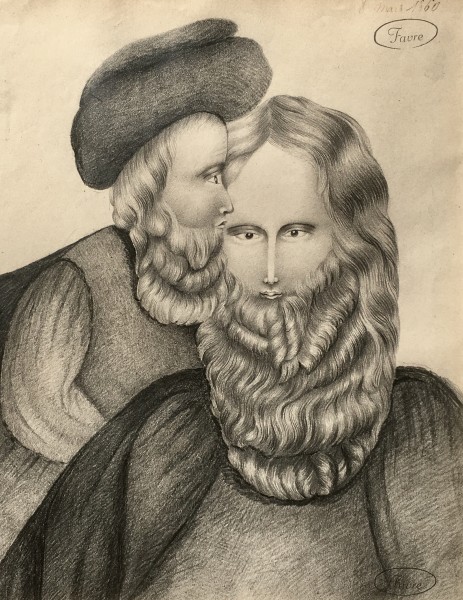

Interest in the art of the mentally ill began in the late 19th century. Psychiatrists and doctors such as Walter Morgenthaler and Hans Prinzhorn – who both also collected – had begun to appreciate not only the extraordinary works by patients but the therapeutic benefits that these drawings and paintings seemed to offer.

Yet in spite of such enlightening thinking, it remained a male world, with the discoverers and propagandists of the genre appearing to treat the work of creative women patients as inferior: famously Prinzhorn eliminated his only chapter on the work of a woman – Else Blankenhorn – from his book.

Expert Cara Zimmerman, in a piece for Christie’s, lists the top Outsider artists to look out for – starting with Henry Darger who grew up in an asylum for children and secretly wrote a monumental illustrated book about a child slave rebellion on an imaginary planet, In the Realms of the Unreal, discovered by his landlord. Other names -in the top 10 list include Bill Traylor and William Edmonson, (both born slaves) William Hawkins and Adolf Wölfli. Only one – Judith Scott – is a woman.

Women outsider artists remained outsiders of the outside. Part of the purpose of the Vienna exhibition was to set this right – Flying High was almost exclusively devoted to female artists.

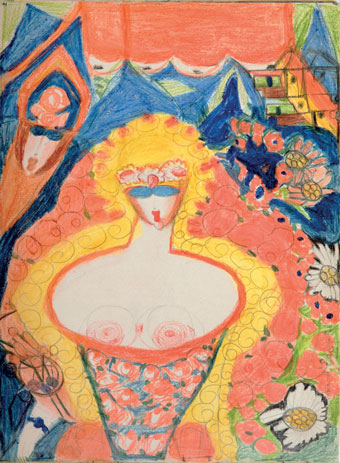

There was also here one solid link with Austria’s imperial history. The undoubted ‘star’ of the show was Aloise Corbaz, the tragic governess who became infatuated with Kaiser Wilhelm II after serving in the Imperial Household for a short period.

She created an imaginary romance and recorded it after her incarceration in a mental asylum in brightly coloured crayon drawings, many of which have softly pornographic elements. The gay, childlike abandon of Corbaz’s art tends to hide the mental anguish of this young lady and this is not uncommon – Giuseppina Pastore, Marilena Pelosi and Martha Grunenwaldt – were among the artists represented in Flying High whose works at first appear happy and vibrant but on closer inspection reveal dark and disturbing elements.

It is possible that when the current pandemic abates, a new generation of Outsider artists will emerge. Who knows? The therapeutic power of art is well attested. Today’s Bethlem hospital in south London has studio facilities for art, woodworking and textiles, and an on-site art gallery that is well worth a visit when all this is over. But you won’t find any works by Dadd hanging there – they have become far too valuable!