In this three-part series, Orchard Times scribe Oscar Rickett investigates the history of Dunwich: Britain’s wannabe Atlantis. This is the second instalment. Here’s Part One.

Man vs. Sea

At the beginning of 1286 Dunwich was hit by its first major storm. Fortifications against the sea had been built but were overturned. In his elegiac book, The Rings of Saturn, which charts a walk through East Anglia, the late German author W.G. Sebald comes to the coast, where he reflects on the storm:

One cannot say how great was the sense of security which the people of Dunwich derived from the building of [their] fortifications. All we know for certain is that they ultimately proved inadequate. On New Year’s Eve 1285, a storm tide devastated the lower town and the portside so terribly that for months afterward no one could tell where the land ended and the sea began.

Sebald’s words rang true even as I looked out across the beach and the banks on a calm day. The flatness of the landscape played tricks on me and it seemed difficult to tell, even when all was well, where the sea ended. It was as if the sea had used the flat dunes and water meadows as a disguise for its encroachment. During the storm of 1286, almost a hundred metres of land on the eastern side of the town followed its companion buildings into the North Sea.

The catastrophe of 1286 was followed in 1328 by an even greater one, more terrible than anything that had come before. More than 400 houses and three churches were swallowed by the sea, while the entrance to the port was totally blocked up. Having made the town rich, the sea was taking it back, burying it under sand and shingle, laughing in the face of the people and their buildings as they floated and sunk, unable to swim to higher ground.

From then on, Dunwich faded, as more and more of it gradually dropped off the cliffs. The town became a village and in the centuries that followed the great storms, thirteen more churches sank beneath the waves, their crosses and altars devoured by a hungry Poseidon like so many Big Macs at a McDonald’s. It is strange to relate that the only things that survived were the walled well-shafts, which for centuries, freed of what had once trapped them, “rose aloft like the chimney stacks of some subterranean smithy, as various chronicles report, until in due course these symbols of the vanished town also fell down” (Sebald).

Fish Tales

Some four-hundred years later, when Daniel Defoe visited Dunwich in the 1720s he noted that “fame reports that once they had fifty churches in the town; I saw but one left, and that not half full of people”. Fame had exaggerated, but the fall from grace was stark. For Defoe, the ruin of Dunwich was particularly poignant because it had been brought about not by human folly but by natural causes. To him, the downfall of once great cities lacked the tragedy of the downfall of Dunwich:

The ruins of Carthage, of the great city of Jerusalem, or of ancient Rome, are not at all wonderful to me. The ruins of Nineveh, which are so entirety sunk as that it is doubtful where the city stood; the ruins of Babylon, or the great Persepolis, and many capital cities, which time and the change of monarchies have overthrown, these, I say, are not at all wonderful, because being the capitals of great and flourishing kingdoms, where those kingdoms were overthrown, the capital cities necessarily fell with them; but for a private town, a seaport, and a town of commerce, to decay, as it were, of itself (for we never read of Dunwich being plundered or ruined by any disaster, at least, not of late years); this, I must confess, seems owing to nothing but to the fate of things, by which we see that towns, kings, countries, families, and persons, have all their elevation, their medium, their declination, and even their destruction in the womb of time, and the course of nature.

For those in low-lying coastal regions, the battles and concerns of great civilisations are more often than not offset by the battle to prevent your family drowning. In this, the Suffolk coast shares a concern with the coastal communities of the Netherlands.

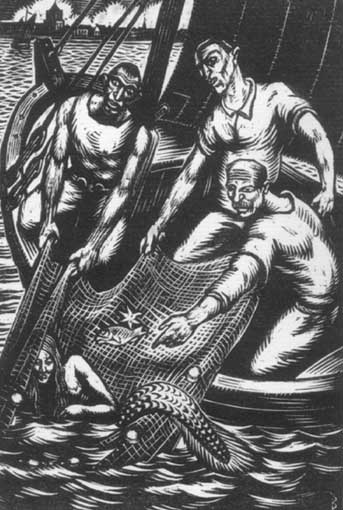

The Dutch province of Zeeland lies below sea level. Its flag shows a lion emerging from the water (half of the lion is still in the water, so there is a suggestion that it could still drown) and its motto is “I struggle and emerge”, which leaves you in no doubt as to what the primary concern was for the people of the province. One folk tale from Zeeland, “The mermaid of Westenschouwen”, tells of fishermen who catch a mermaid in their nets. She is brought back to land and everyone in the town marvels at her. But her merman husband misses his mermaid and every day his voice can be heard calling for her, telling the people of the town he wants her back. Unlike Tom Hanks in Splash, the fishermen refuse to return the mermaid and they are shouted at one last time by the mermaid’s husband:

Westenschouwen,

You will regret,

That you have taken my wife.

Westenschouwen

Will drown,

Only the plump church-tower will remain

And this is exactly what happened. The village was lost and the inhabitants drowned. The people of Zeeland, wanting to feel that they had some control over their fate, told the story of the mermaid as a way of warning of the sea’s power. Respect the sea, the story says, and it might not get you.

This series will continue at the same time, in the same place and with predominantly the same theme, next week.