Dora Carrington: Beyond Bloomsbury

While the great Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington has long been out of the shadows Dora – the ‘other Carrington’ (1893-1932)- remains an obscure figure.

It’s 30 years since her previous major show at the Barbican but late last year she was propelled quite literally into the spotlight once more with the release of Pedro Almodóvar’s award winning film, The Room Next Door, with its reflections on assisted dying. The director has long been intrigued by Carrington’s complex and fragile life as an artist living in a patriarchal society. Her obsession with the writer Lytton Strachey – which led ultimately to her own suicide – is one of the underlying themes of the film.

Released on the eve of a new exhibition devoted to Carrington at Pallant House, a gallery in West Sussex, the timing could not have been better. “It was extraordinary,” said co-curator Anne Chisholm. “We didn’t know that the film was in the offing.”

Both Carrington and Strachey were part of the Bloomsbury Group, a collection of intellectuals in the early 20th century, mostly Cambridge-educated, who had the means and freedom to explore unconventional lives centered around love, art, and ideas.

Carrington’s own life had started conventionally enough in a middle class home and at the Slade art school, where she was the only female in a class tutored by the traditionalist Henry Tonks. She was an exceptional painter and draughtswoman and by the age of 19 had won a scholarship and prizes for two portraits.

One of the great works on show at Pallant House is Carrington’s brilliant painting of Mrs Box, done at the age of 26, on loan from the National Portrait Gallery. It is an endearing picture of a Cornish farmer’s wife, Mrs Box, (please use this image) whom she met on a walking holiday. “She is full of vigour, fetches the cows from the marshes every day,” wrote Carrington who painted her in full Sunday finery with a look of deep resignation.

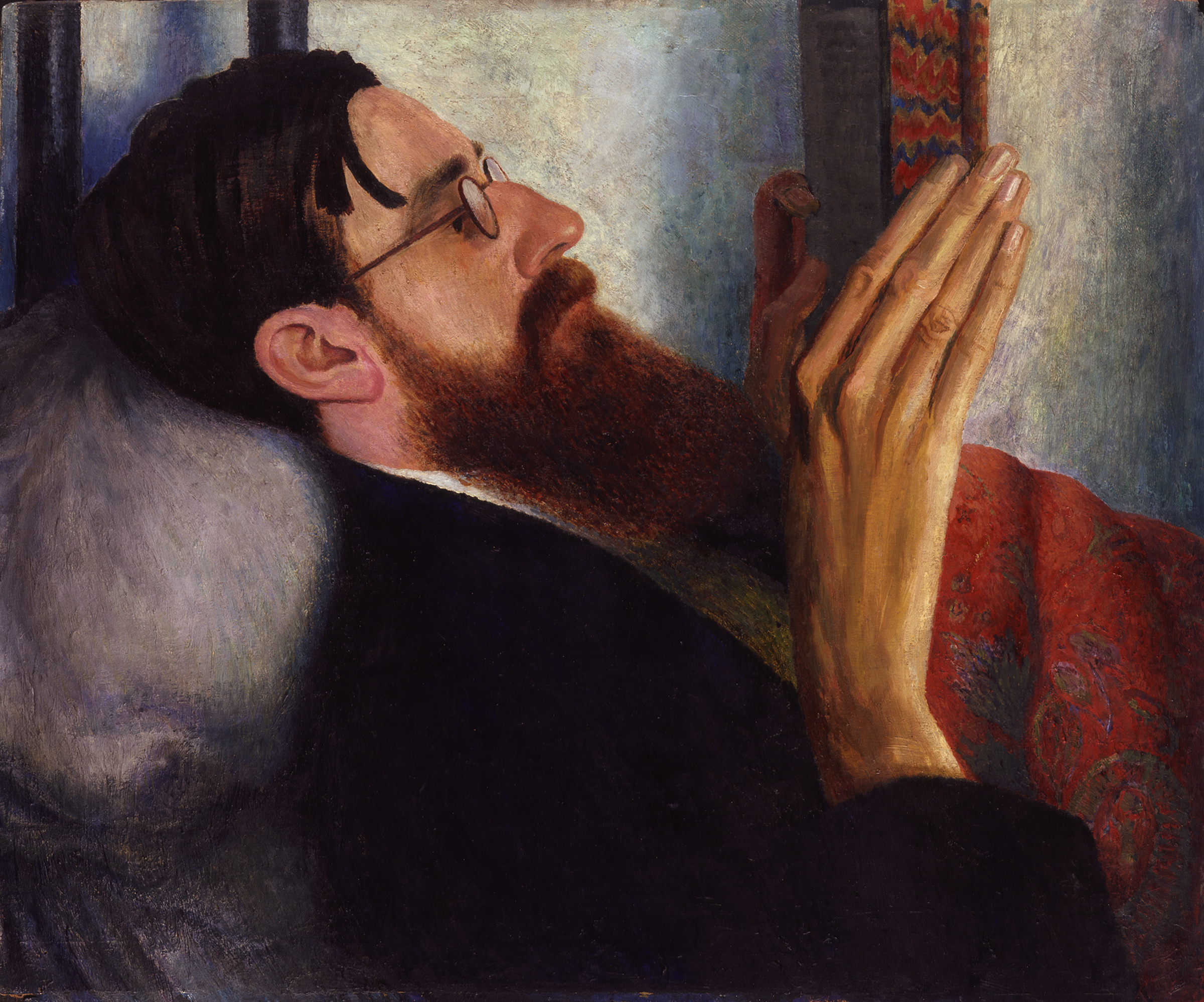

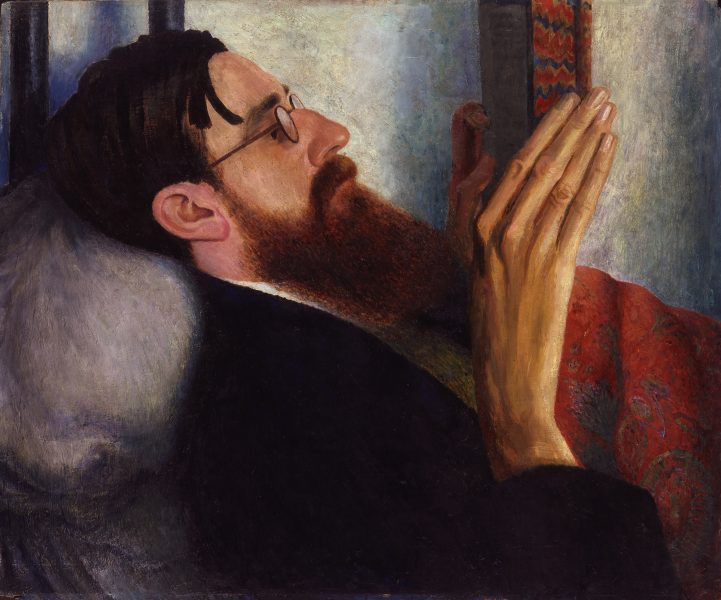

However, Carrington’s artistic journey took a complex turn when she broke free from the constraints of her early life and embraced the innovative movements of the early 20th century. Her style fluctuated between Futurism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Surrealism, but never found a lasting home. and never returned to the great early portraits such as that of Mrs Box and Lytton Strachey, the most iconic image known of the writer and also on loan from the NPG to Pallant House.

Carrington’s art was overshadowed by her complicated love life. She was openly bisexual but also deeply in love with Strachey and lived with him platonically for a few years. Among visitors to their Wiltshire home was another Bloomsbury creature, Ralph Partridge, who fancied Strachey. At the age of 28 Carrington married Partridge to cement a three-way relationship – curator Ariane Bankes called this “the Trinity of Happiness.”

The final room of the exhibition looks at Carrington from the perspective of her home making at Ham Spray house in Wiltshire where this trinity settled in 1924. Here, Carrington created imaginative decorative schemes and experimented with ‘tinsel pictures,’ glass paintings inspired by folk art. It seems as though Carrington turned to homemaking when her interest in painting waned.

Strachey, always delicate in health, remained at Ham Spray until his death in 1932. His demise left Carrington heartbroken and depressed. She took her own life the same year, leaving a trinity of great portraits but hardly one of happiness.

Until April 27th at Pallant House, Chichester, West Sussex, UK

www.pallanthouse.org.uk

A Renaissance ‘Where’s Wally’

Among the highlights of the 2025 exhibition programme announced by the National Gallery of Ireland, including exhibitions devoted to Pablo Picasso, J.M.W. Turner and two Irish modernists is the unveiling of the newly conserved masterpiece by the Renaissance painter Ludovico Mazzolino (1480-1528).

Mazzolino’s Crossing of the Red Sea, a rare large late work of 1521, uses all the dramatic techniques available to the painter in this fantastical vision of the famous legend. The painter uses a bird’s eye view of the action, flattening the perspective in a rather un-Renaissance manner. The writhing mass of Egyptians and horses plunged into the sea contrasts with the motionless crowd of the Israelites on the banks, above whom God works his magic. Colour is of course called into use in this magnificent drama, but here the painter is restrained and uses a palette limited to blues, whites and earth tones.

The painting has never been on show due to conservation problems. Speaking to the Art Newspaper, curator Aoife Brady, said: ” It’s quite a wild thing, a sort of Renaissance Where’s Wally? The gallery bought it in 1914 so it’s a very early part of our collection, but I can find no record that it has ever been on display.”

Thanks to a European Fine Art Foundation (Tefaf), grant, the National Gallery of Ireland will finally be able to unveil this masterpiece in mid February. It is noteworthy that the immense cost of the restoration is undoubtedly why despite repeated appearances at auction, this masterpiece failed to sell. When the hammer fell at £36.15 in 1915, Ireland got an expensive bargain.

On show from 15th February to 6th July at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

www.nationalgallery.ie

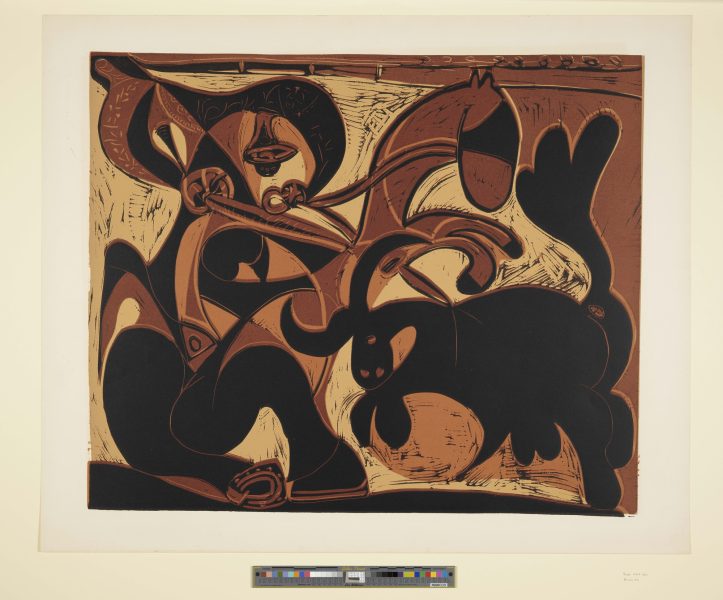

Picasso: Printmaker

The latest Picasso show at the British Museum is devoted to some of the 2,400 prints he made over his lifetime. It spans the gamut of this considerable body, featuring works from the turn of the century through Cubism and up to the last decade of his life when at the remarkable age of 87 he published the 347 Suite, a series of etchings and drypoints made in the course of just nine months. The series baffled art historians and reporters at the time of its publication by Phaidon. Even though Picasso was notorious for his ability to churn out works quickly – he could manage three oil paintings in a single day – Rembrandt produced no more than 300 etchings in his lifetime.

There was also a whiff of scandal because the octogenarian had deliberately included provocatively erotic works. Despite the porn – or possibly because of it – the 347 Series was popular and toured America the same year.

The British Museum, incidentally, has not chosen to exhibit any of the 20 works which were deemed particularly offensive at the exhibition.

Such material aside, it often seems that we can never get enough of the great Spanish painter. Other major Picasso exhibitions this coming year include ‘Picasso: From the Studio’ at the National Gallery of Ireland, which looks at Picasso through the prism of his working environment. In March Hong Kong’s M+Museum explores the relationship between Picasso and Asia placing loans from the Musée National Picasso in Paris alongside contemporary Asian works. September sees Tate Modern London hosting ‘Dances’ celebrating Picasso’s iconic 1925 painting The Three Dancers while Charleston in Lewis offers Collecting Modernism: Pablo Picasso to Winifred Nicholson in the same month.

Until 30th March at the British Museum, London, UK

www.britishmuseum.org

Letizia Battaglia: Life, Love and Death in Sicily

All considered it is astonishing that Letizia Battaglia (1935-2022) lived to the grand age of 87. In her forties, as a photojournalist she flirted almost daily with danger, recording the mafia’s terrifying regime in her native land.

Born in Sicily, Battaglia had to flee to Milan when her first husband tried to murder her for having an affair. (He would probably have gone unpunished if he had succeeded.) On her return to Sicily in 1974 she found work with l’Ora, a left wing newspaper in Palermo.

The Mafia’s rackets in Sicily were booming again after a difficult time in the 1960s.

The Photographers Gallery picks up her story as Battaglia recorded daily life in Palermo – the parties, dances, children, festivals and bloody gang warfare. On some days she recorded up to five murders.

She lived in constant fear of assassination. “You no longer knew who your friends or enemies are,” she once told a reporter. “In the morning you came out of the house and did not know if you’d come back in the evening”.

When politicians and judges were assassinated and mobsters, Battaglia was often first at the scene. Among the 60,000 images she took there’s a lot of blood, thankfully she mostly used black and white out of respect for the dead.

Alongside the images of gun toting Mafiosi, it’s also a record of life in the shadow of violence and the effect on society, particularly children, as in the difficult image of a boy with a stocking over his face pointing a gun towards Battaglia’s camera.

Until February 23rd at the Photographers Gallery, London, UK.

www.thephotographersgallery.org.uk

Art Heists (book review)

Late last year, thieves blew open the door of a Dutch gallery in an attempt to steal four screen prints by Andy Warhol. In the botched raid, they only got away with two but managed to damage all the works. “The bomb attack was so violent that my entire building was destroyed” gallery owner Mark Peet Visser told the press. “ And when they ran to the car, the artworks wouldn’t fit inside it.”

Warhol prints are a favourite for thieves. According to a new book by Susie Hodge, Art Heist, more than 40 were stolen between 2008 and 2016. One reason for their value, says Hodge, is the rapidly improving quality of printing that enables criminals to produce fakes that most people cannot detect.

The book is peppered with botched heists, some of which are mildly amusing but most are tragic. One particularly sorry story is that of Olga Dogaru, the mother of a Romanian member of a gang which stole six masterpieces from Kunsthal Museum in Rotterdam in 2013. When her son Radu was arrested after having stashed the paintings at his home in Romania, Olga threw all seven pictures into a furnace, reducing the priceless works to ashes. They included a Picasso, two Thames scenes by Claude Monet and a portrait by Freud.

This fully illustrated book is rich in detail and filled with photograph of pictures (many lost forever) that the art historian has unearthed from the archives.

Art Heist by Susie Hodge, £20, published by Quarto.

Noah Davis

The American artist Noah Davis (1983 – 2015) gets a show at the Barbican this year. Born in Seattle, in 2004 he moved to Los Angeles where he co-founded the Underground Museum, he felt it his duty to record “the people around me.” Using a range of materials and techniques including vintage photographs bought at flea markets, his images have a dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish quality.

Notwithstanding his pledge to record the reality around him, his characters are often fictional but they do things that people in LA liked to do: dive into swimming pools; dance; contemplate public art. Davis moved between painting styles, often using unorthodox techniques and a noticeably diverse palette.

Davis liked to think that art was for everyone. In 2012, he co-founded the Underground Museum with his wife Karen – now a revered institution in the historically Black and Latin neighborhood of Arlington Heights. The centre was free and open to all and here Davis made his studio and offered residencies.

He convinced the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art to lend works and planned 18 exhibitions for his museum motivated by the desire to “change the way people view art, the way they buy art, the way they make art.”

Some 50 of Davis’s works can be seen at the Barbican: they chart his interest in politics and current affairs, everyday life, ancient Egypt, family history, the racism of the American media, art history and architecture. The paintings are positioned alongside Davis’s experimentations in sculpture and works on paper and there’s a fascinating selection of his eclectic source material, on display for the first time.

Exile: Artist perspectives

What effect does exile have on the creative abilities of artists? Does it render them less capable or make their work more distinctive? At this year’s Venice Biennale curator Adriano Pedrosa chose to fill a room with works by a diverse collection of Italians who had all made their homes abroad. This worked well with the theme of the Biennale which was “Foreigners Everywhere.” Artistically, however, the works were hard to praise. At Louvre Lens, an offshoot of the Paris museum, exile is seen in the context of a forced departure – be it for political, economic or health reasons – and so there’s a broader platform.

The artists represented range from Homer and Victor Hugo to Marc Chagall and Barthélémy Toguo. Their works examine the complexities of being prooted as well as being planted in an new environment. Featuring more than 200 works, the exhibition is intended as an immersive experience, highlighting artistic, literary and philosophical creations spanning the centuries.

Until the 20th January at Louvre, Lens, France.

www.louvrelens.fr

Credits

Letizia Battaglia, Desperation of a son, Palermo, 1976, Courtesy Archivio Letizia Battaglia

Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey reading, 1916, Vational Portrait Gallery

Dora Carrington, Mrs Box, 1919, Trustees of the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery

Ludovico Mazzolino, The Crossing of the Red Sea, 1521, National Gallery of Ireland

Duccio, Christ and the Woman of Samaria from the Maestà series of panels , 1308-11, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

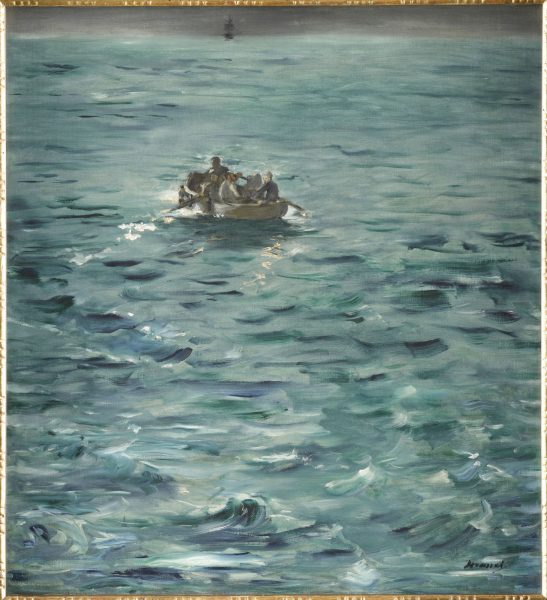

Edouard Manet, Rochefort’s Escape 1881, Musée d’Orsay

Pablo Picasso, Pike, 1959 Succession Picasso