Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers

A major part of the National Gallery’s 200 year anniversary celebrations is the stunning Van Gogh exhibition, Poets & Lovers. It is also the centenary of the acquisition of Sunflowers in 1924, when as co-curator Christophe Riopelle says, the National Gallery was “trying to be more modern”.

All the 47 paintings and drawings on view were created after Van Gogh moved from Paris to Provence in 1887 and rented a house in Arles. Within a year he had been admitted to the asylum at St-Remy following the disastrous visit of Paul Gauguin.

Laudably the show does not rake over the old coals of their punch up and the ear cutting but instead brings us a fresh picture of the artist as a consummate professional who intended to rewrite modern art with his work.

The story that unfolds as you move from room to room is not of a broken and tragic artist who never sold a painting but one who fully believed in himself and his future success. “He was convinced he would have a public,” says curator Cornelia Homburg.

Without any sense of his impending fate, Van Gogh launched into a frenzy of activity, creating no less than 350 works in 27 months (nearly one every two days) including some of his most iconic paintings: Chair, Sunflowers and Starry Night. All this while finding time to write dozens of illustrated letters to friends and fellow artists as well as his brother Theo.

The show opens however not with sunflowers but two of the portraits that give it its title: the Lover and the Poet and it goes on to explain and explore these images and how Van Gogh chose the subjects who to him represented such archetypes.

Prior to this move to southern France, Van Gogh had been steeped in the new art movements in Paris. Now he wanted now to plant his own identity on the art world and colour would be one of his servants in this quest: “the painter of the future is a colourist such as there hasn’t been before,” he wrote to Theo.

The world famous pictures aside, the show features less known works, including many painted in gardens. The public garden at Arles and the small garden surrounding the asylum are both elevated into places of greater emotional significance by the use of bold and sometimes frenzied brush strokes as well as the insertion of imaginary figures and lovers.

One of the best known pictures, that of the Yellow House, opens a new chapter in this story. In advance of the much anticipated visit of Gauguin, whom he admired enormously (it was not reciprocated) Van Gogh began his great project, a massive “decoration”.

The term translates badly. Decoration was not about throwing up wallpaper but a serious art form. In Paris Van Gogh had studied the murals of Eugene Delacroix and regarded the Frenchman as a great decorative artist. Seurat, he thought, was another and Van Gogh monitored him closely, repeatedly writing to Theo to ask what the pointillist was up to.

Thus be began a series of works at the Yellow House that were colour coordinated in complementary colours – red/green/yellow/blue etc – and include Chair and no less than 11 Sunflowers – four in one week. The choice of humble local items was deliberate and part of his vision of a new art.

Surprisingly this is the first time that the National has staged a show devoted exclusively to Van Gogh. It’s simply not to be missed.

Until January 19th at the National Gallery, London, UK

India ‘s turbulent time of change

The main galleries of the Barbican are devoted to the work of 30 modern Indian artists during a period of major cultural and political change. The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1978 features nearly 150 works of art across a range of media.

The show charters how artists responded to the first state of emergency (1975) and India’s emergence on the global stage as a nuclear power (1978).

The many themes that are explored include urbanisation (the result of population growth), gender and sexual challenges and norms; rural life; caste issues and the rise of divisive politics.

“The show examines how artists’ practices negotiate with what is happening around them. You go on a journey that the artist takes understanding these issues, ” says curator Shanay Jhaveri.

Film and photographic works include scenes of young activists gathering during the time of censorship, queer men trying to find a place in society, lovers crossing mountains to meet forbidden partners.

“I wanted to represent also how life goes on while these major events are taking place. It’s really about moving between the realms of the home and the street…..here you can see all these responses to all these issues in a place that is safe and comfortable, ” says Jhaveri.

Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970, which runs alongside the exhibition links to our second show in the Barbican’s Curve gallery. This presents the imaginary story of a woman living in a colonial outpost where she refuses to follow the rules. The site specific show by Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum draws on the architectural history of the Barbican, film noir and crime novels to tell the story of Bettina in a series of life-size dioramas. This is Sunstrum’s first major UK commission and the outcome of the story of her alter ego Bettina is suggested by the show’s title: It Will End in Tears.

Both shows are at the Barbican, London, UK until 5th January, 2025.

Hilma af Klint

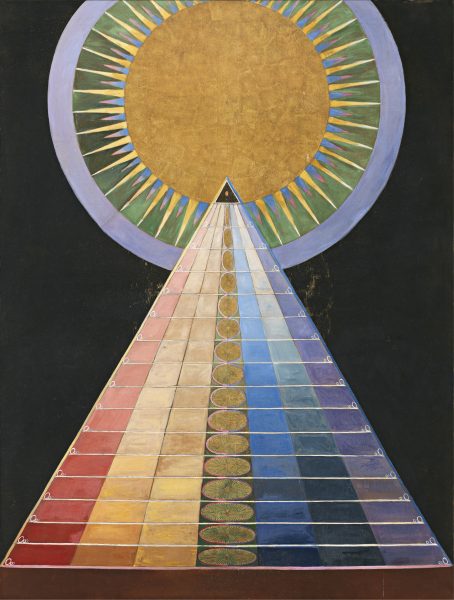

Above: Hilma af Klint. Retablo, Retablos, 1915. Oil and metal leaf on canvas. Courtesy The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm

Once again a female artist has stepped out of the shadows and helped rewrite art history. Swedish-born Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) is now often held to be Europe’s first abstract painter whose works pre-date those of Mondrian and Kandinsky (traditionally assumed to hold this title) by decades.

Her current show at the Guggenheim, Bilbao, spans her work from early traditional works through automatic drawings up to the final watercolours. But the monumental series of paintings made for the “Temple” are the most exciting part of the story.

Af Kilmt was part of a group of women called The Five who met to pray and conduct séances in Stockholm at the turn of the century. Spiritualism in many forms was fashionable at this era which saw the birth of Theosophy and the anthroposophical movement of Rudolf Steiner, whom af Klint met.

It was during these sessions that af Klint, who made her living painting conventional landscapes and portraits, received messages from what she called the High Masters to create a series of painting for the “Temple.”

She did not know what the Temple was but followed the instructions and began work on the series now known as ‘The Paintings for the Temple’ which broke all the rules of art.

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

Steiner, who later saw the Temple paintings, was lukewarm about the works although he did keep photos which some art historians believe he may have later shown to Kandinsky.

The remainder of her life was devoted to making sense of the new language of angels that she believed had been delivered to her. In her notebooks, af Klint assiduously describes the secret energies of atoms and plants, believing ( like Steiner) that the spirit world could be understood by careful scientific observation.

That however is not the end of the story. Following a show at the Guggenheim New York in 2018 which propelled af Klint to fridge magnet fame and rocked the art world, questions began to arise as to whether af Klint was the sole author of all the works attributed to her. The quarrel over her legacy – in other words who owns the rights and gets the money – is working its weary way through the Swedish courts.

As a final note, it is ironic given af Klint’s meteoric rise to fame and posthumous fortune that in 1970 her paintings were offered as a gift to Moderna Museet i Stockholm but the donation was declined. A clairvoyant might have been useful.

Until February 21st at the Guggenheim, Bilbao, Spain

Scent & the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites

Above: Dante Gabrielle Rossetti, Proserpine, 1881-1882. Oil on canvas, Birmingham Museums Trust

A new exhibition in Birmingham springs from a book linking art and our sense of smell. Dr Christina Bradstreet, author of Scented Visions: Smell in Art, 1850-1914, is the curator of this curious show.

The link between scent and memory, and how certain smells evoke strong emotions, has long been recognised. For the Victorians, sensory details in paintings were thought to be able to trigger a variety of visceral responses. Smell loomed large in people’s minds in the 19th century. The theory that diseases cholera and the Black Death were caused by miasmas – ‘something in the air’ – had led to the drive for sanitation reform and rise in the perfume trade.

A pseudo science of olfaction and the belief you could see smell inspired some artists – specifically the Pre-Raphaelites – to picture scent in order to better know and control it. Fragrant imagery in the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Frederic Watts, Edward Burne-Jones and others set the trend for a preoccupation with scent that emerges in paintings and posters.

Until 26th January 2025 at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, UK

Paula Rego

Acrylic on canvas

223 x 203 cm

Serpentine & FCG Catalogue, 1988: 220 x 200 cm

Two concurrent exhibitions of the work of the Portuguese/British painter Paula Rego highlight her new found status as an exceptional figurative artist. Paula Rego – Power Games, at the Kunstmuseum, Basel, focuses on one of her dominant themes: the ruling elite, male hierarchies and power play. This harks back to an extent to her native country Portugal. Rego (1935–2022) born in Portugal at the time of the dictator Salazar, began life in a male dominated and tightly controlled country a world away from today’s liberal Lisbon society.

Her mother was a competent artist but Rego was not encouraged to take up a career, least of all in art. Strong willed and determined, she argued her way into the Slade art school after the family moved to England. Yet early influences haunted her and many works hark back to her native land where men almost invariably controlled the lives of daughters and wives.

The extensive exhibition in Basel presents around 120 paintings, pastels and collages, including many overt political works aimed at the Iberian dictators Salazar and Franco such as Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960) and The Dogs of Barcelona (1965). Former Tate director Nicholas Serota said of Rego that she: “had taken her own childhood experiences, memories, fantasies and fears, and given them universal significance”.

In 1990 Rego became the first Associate Artist at London’s National Gallery where she likened herself to a poacher. “I would creep upstairs [into the gallery] and snatch things, and bring them down to my basement, where I could munch away at them,” she said. During this time she began to appreciate “just how good, how incredibly complex and profound” Old Master paintings could be.

Prior to this initiation, Rego had chiefly been interested in popular art and folk art. The first stories that fired her imagination were native Portuguese folk tales told by her grandmother and often involving cruelty which – like many children – she found gruesomely fascinating.

The second exhibition, Paula Rego: Visions of English Literature, at the University of Nottingham, delves into the sources that were essential to her work: “I always need a story. Without a story I can’t get going.” Sketches, etching plates and Rego’s childhood copy of Peter Pan transform these seemingly innocent sources into startlingly original and unexpected pictures. Menacing oversized creatures leap out from the paper in works such as Little Miss Muffet and Three Blind Mice, while Rego’s depictions of Neverland verge on the hallucinatory imaginings of Peter Bruegel. In Jane Eyre, a work which she discovered initially through the prequel Wide Sargasso Sea, the Creole beauty Bertha (who takes the place of Jane) is married by the young Rochester for her money and ends up as the “madwoman in the attic”.

These complex imaginative works, which combine fantasy and imagination, innocence and cruelty, explore the complex lives and experiences of women in particular, in all its strangeness and mystery.

Paula Rego Power Games is at the Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland until 21st February 2025. Paula Rego: Visions of English Literature is at the University of Nottingham until January 5th 2025.

Churchill’s studio sanctuary

Above: Churchill’s studio at Chartwell

Nestling in the folds of the Kent countryside is the delightful National Trust property, Chartwell, former home of Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine.

Much visited throughout the summer, winter is the better time to beat the crowds and one of its chief attractions is the garden studio where Churchill painted some of the hundreds of pictures he made after discovering the therapeutic benefits of art. He painted 550 pictures – not many of them are frankly very good but considering his political life and his role in two world wars, they aren’t that bad.

He fell upon painting accidentally thanks to his sister – a watercolourist – after hiring a house in Surrey for a family holiday. It was 1915 and his political career was in low ebb following the disastrous Gallipoli campaign.

His only self portrait, on show in the studio, is a somber image of a man beset by what he called his ‘black dogs.” Painting eased his depression and he was advised and encouraged in his art by his London neighbour Sir John Lavery, and later also Walter Sickert. Lavery told him to “borrow art and copy” and he tried that approach often, making many impressionistic and post impressionist attempts which can be seen at Chartwell.

“If it weren’t for painting”, Churchill once told former Tate John Rothenstein, “I couldn’t live. I couldn’t bear the strain of things.”

After losing his Dundee seat in 1922, Churchill retired briefly to the south of France where he devoted himself to painting and writing The World Crisis, his memoirs of World War I.

Churchill claimed he had painted only one picture during the Second World War – a view of Marrakesh and the Atlas Mountains. He later gifted it to Franklin Roosevelt, with whom he had stayed in Morocco. After Roosevelt’s death it was sold to Angeline Jolie and Brad Pitt, thus establishing a new fame. On their divorce, it was consigned to Christie’s for auction and hit the headlines making a phenomenal £8 million. It is sadly not among the works at Chartwell: “We couldn’t afford to buy it,” says the studio guide ruefully.

Churchill painted as therapy. He had no great concern or care to improve what he called his “daubs.” His first oil painting, on show in the studio, is about the same level of competence as the last done some 30 years later.

“Success is going from failure to failure without losing enthusiasm,” he once wrote and it could be applied to his art. But he did twice have paintings accepted for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition and was elected as an Honorary Academician Extraordinary in 1948 when his book Painting As A Pastime was published. A visit to Chartwell and the studio is a delightful peek into this great man’s world and there’s also a discounted ticket price for garden-only entry available year round.

Above: Hever Castle

A glimpse into the life of another famous name of a very different nature can be found by popping along to nearby Hever Castle. This is the childhood home of Anne Boleyn and according to historian David Sarkey, “the place where the Reformation began. ” Specifically Sarkey is referring to Anne Boleyn’s private quarters (and bedroom) which have recently been given a makeover.

Textiles are at the centre of this refurb, with tapestries, damasks and ‘Turkey’ carpets now lining the walls and window ledges while authentic looking coir matting covers the floors. The overall effect is pleasing and fresh but textile buffs will come away disappointed. Ahe tapestries are printed reproductions of originals from the Victoria & Albert Museum, the damasks are likewise printed rather than woven while the ‘Turkey’ carpets are definitely 20th century. One still sported its price tag.

www.nationaltrust.org.uk/chartwell and www.hevercastle.co.uk

Paradox Museum opens

London is the latest international city to get its own Paradox Museum, a sort of cross between a theme park and a Kusama style infinity room experience. Located opposite the world famous Harrods department store, it’s all about mind-bending visual illusions. There’s a Camouflage Room where you seem to disappear into the walls, a mirror maze and a Paradox Tunnel where the simple task of walking in a straight line becomes nearly impossible. Combining the worlds of science, art, and psychology, the museum is the new place to grab those essential Instagram photos.

The Paradox Museum is at 90 Brompton Road, London, UK

credits

Lead picture: Vincent van Gogh. Starry Night over the Rhône, 1888. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

,