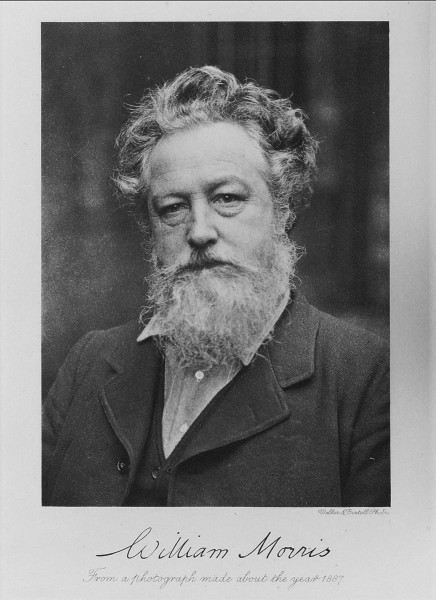

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the designs of William Morris – his trellises and willows and honeysuckles – are a little out-of-date and irrelevant. Popular designs like Strawberry Thief adorn cushions and mugs but do they really fit the modern interior? Surprisingly, not only have these botanical themes made a massive comeback but Morris himself has been enjoying a new wave of popularity – as an environmental prophet and anarchist.

At the Venice Biennale in 2013 Morris’s sense of outrage at capitalism was summed up by a mural portraying him throwing Abramovich’s yacht Luna into the lagoon.The work by Jeremy Deller, We Sit Starving Amidst Our Gold, was read as a critique not only of the yacht, which earlier had been parked so that it blocked the view of the lagoon, but also the crass commercialization of art.

Morris has also recently been extolled as a precursor of green theory according to biographer Ruth Kinna. If Morris were alive today, there’s no doubt he would be standing shoulder to shoulder with the Climate Extinction protestors. Unfortunately he was 170 years too early but he foresaw the ill effects of industrialisation: “When our green fields and clear waters, nay the very air we breathe, are turned… to dirt…let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we die – choked by filth.”

The wide natural world in which he had grown up cantering his pony through Epping forest, was being destroyed before his eyes and the common man enslaved to carry out this destruction. Observing the ill effects of factory work on people, Morris also realised that a healthy environment was linked to psychological as well as physical health: that the landscape itself could lift spirits and contributing to psychological equilibrium. Obsessed with the pollution, the congestion, and squalid industrial waste produced by the Industrial Revolution he retreated artistically into a medieval utopia. Fighting the evils of the ‘modern age’ became, in due course, linked to his entire design ethos and underpinned his life’s work.

In 1854, aged 20 Morris and Edward Burne-Jones had travelled to see the cathedrals and churches of France and Belgium. Inspired by these buildings, created under the guild system, they pledged to abandon their theological studies and devote their lives to art. “Fired with the medieval idea, Morris spotted that the craft system offers labour that can be dignified,” says historian Peter Cormack.

Seven years later along with fellow ‘fine art workmen’ he founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co – later to become internationally famous as Morris & Co. “We found that all the minor arts were in a state of complete degradation … with the conceited courage of a young man, I set myself to reforming all that,” wrote Morris.

A new exhibition Inspired By Nature at the Grade I Standen House, a National Trust property, is a chance to look at Morris’s legacy both in the arts and as a environmentalist.

Standen House is a particularly good place to appreciate the revolutionary nature of Morris’s ambitions because the house, created by his close friend the architect Philip Webb (who had also built the Red House for him), breaks all the rules of an important country house design.

Instead of a sweeping driveway leading to an impressive grand frontage, the first building you come to at Standen is – a barn. Built in 1892-6 for the wealthy Beale family, rich industrialists (ironically) from the north, Standen is furnished from top to bottom with products and designs from Morris & Co and the current exhibition contains a mock up of the showroom in London at which the Beales would have chosen their fabrics and wallpapers. A portrait of James Beale hands in one of the main passages decorated with the famous Trellis design wallpaper – an early design by Webb and Morris.

Art historian Abigail Harrison-Moore explains: “At Standen the first thing you see is a house and barn almost as if Webb and the Beales wanted their country estate to be a home but not a stately one.”

At the heart of the building is a water tower – designed so the house could be self sustaining in water. Internally kitchens and servant quarters are not hidden away in attics and basements but celebrated.

Standen, which also celebrates local materials, was one of the first houses built with electricity. The importance of the relationship between function and beauty is evident in the designs for the lights by Webb that are based on natural forms.

The house is full of examples of works by others in the Morris circle – William de Morgan, William Arthur Benson (William was a popular name) but the common theme in all of the decoration and furnishing is the application of old craft techniques and the celebration of artisan products. This after all was in the DNA of Morris & Co.

One example in particular that Harrison-Moore picks out is the Morris chair several examples of which can be seen. “In itself it typifies all the ideals – an object found in a historic farmhouse changed into a 19th century design that became very popular.”

As you might expect given Morris’ forward thinking views, women designers can be found here. The Garratt cousins who worked at Standen, were some of the very first professional decorators of the ‘fair’ sex doing jobs that were not generally considered right for women.

Morris made a conscious attempt to change people’s lives through his design work. His well known dictum: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful” hides his deeper passion for socialism. His clients would have been shocked if they had known his deep concerns that his own design and decorating business was simply “ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich” but. the economic reality was that only elite clients could afford his products.

It was a dilemma that he never resolved, hoping (in vain) that consumers could be educated into buying less and regarding their purchases as investments. It is the challenge taken up by Terence Conran with his mission to bring good design to the high street. “I have a Morris-like view about not producing things only the rich can afford,” he once wrote. “We should not be deceived by Conran’s image of self-satisfied tycoonery. He has for some years been consumed by Morris-style fury at the failure of successive governments to pay serious attention to design,” says biographer Fiona MacCarthy, curator of the 2015 exhibition devoted to Morris Anarchy & Beauty at the National Portrait Gallery.

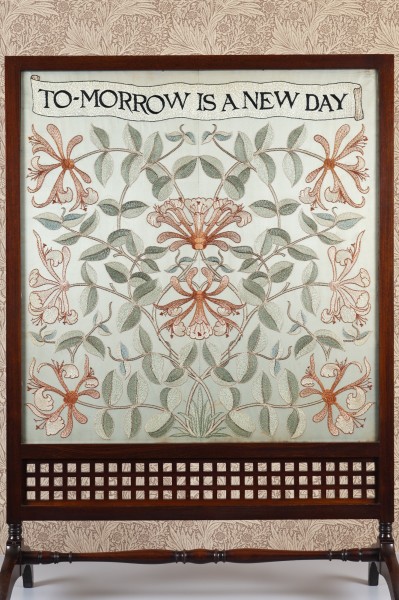

“Apart from the desire to produce beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization,” he wrote. That passion reveals itself as an obsession with the natural world. Form, Morris believed was beautiful only if it was in accord with nature. “I must have unmistakable suggestions of gardens and fields, and strange trees, boughs and tendrils.”

“Morris’s love of nature was a well-spring for his work. He possessed an understanding and deep love of all natural things: flowers, trees, birds, animals and insects,” says Alice Strickland, Standen’s curator.

The exhibition, which also includes exquisite embroideries by Morris’ daughter May, emphasises the importance Morris placed on the revival of traditional skills and techniques including natural dyeing( despite the fact that his company was guilty of using arsenic to make a green dye for wallpapers) in which he took a keen interest rejecting the new synthetic dyes.

“As with other followers of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and aestheticism in general, the key motivator for his art was beauty itself,” says Morris expert Professor Bradley Macdonald. “With that said, beauty – and beautiful designs that draw upon nature – have critical components that remind us of the need for keeping nature intact. This point is definitely implied in Morris’s writings. He clearly felt that humans desperately needed a connection to nature to live a truly human life, and his designs were attempts to keep that connection alive.”

Inspired by Nature at Standen House, Hoathley, West Sussex runs until November 10. The event includes craft workshops, walks through the Arts & Crafts gardens overlooking the Sussex Weald and talks on the significance of trees and plants to Morris. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/standen-house-and-garden/features/morris-and-co-inspired-by-nature-exhibition