More than 10 years in the making, and hugely anticipated, the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi is a momentous event, a milestone for the cultural enrichment of the Emirates and the first museum in the region to present works spanning the whole of human history from Paleolithic times to the 21st century.

While the “rain of light” effect of Jean Nouvel’s 180 metre wide dome, a star patterned “parasol” has seized the headlines, the galleries are the real stars. In truth I rather preferred the original white dome that was shown in model form 10 years ago when the project was first announced.

It was softer, more organic but the engineering problems which Nouvel encountered clearly forced a revision of the structural ideas he started with.

It was softer, more organic but the engineering problems which Nouvel encountered clearly forced a revision of the structural ideas he started with.

The ambition of the Louvre Abu Dhabi to be a ‘universal museum’ is born to an extent from the problems of acquiring art worthy of such an institution when great works are almost impossible to come by (whatever your budget) and some artists are not available at all. The decision taken at the outset to present the works in way that breaks conventions as a cross-cultural series of chapters beginning with The First Villages and moving to A Global Stage is a means of addressing the problem.

The very last exhibit to be installed prior to the week-long opening ceremony in November was Leonardo da Vinci’s La Belle Ferronniere, but our guide rightly determined to focus on the objects that the Abu Dhadi Louvre owns rather than the loans. Among the most important is the glorious Egyptian funeral set of Princess Henuttawy, including her mummified remains, dating from the 10th century BC, and in a remarkable state of preservation.

The ‘universal’ arrangement of the exhibits is obvious in Gallery 6, From the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, where a 15th century Venetian Madonna by Bellini can be seen alongside a 14th century Syrian/ Egyptian basin and an 11th century bronze Lion de Mari-Cha from Spain or Italy standing proudly in front of a Flemish tapestry. Turn a corner and you find 17th century screens depicting the arrival of Portuguese in Japan while in the next gallery I caught the Leonardo out of the corner of my eye as our guide explained an Islamic tilework to us.

“Do not be distracted,” he said, noticing my glance straying but how could one not be distracted by one of the greatest and most beautiful portraits anywhere in the world? Following the highly unusual way of grouping the arts into chapters rather than by type or region requires and immense concentration – but it’s also a good reason to make another visit.

Other must see exhibitions this winter:

Living with Gods: People, places and worlds beyond

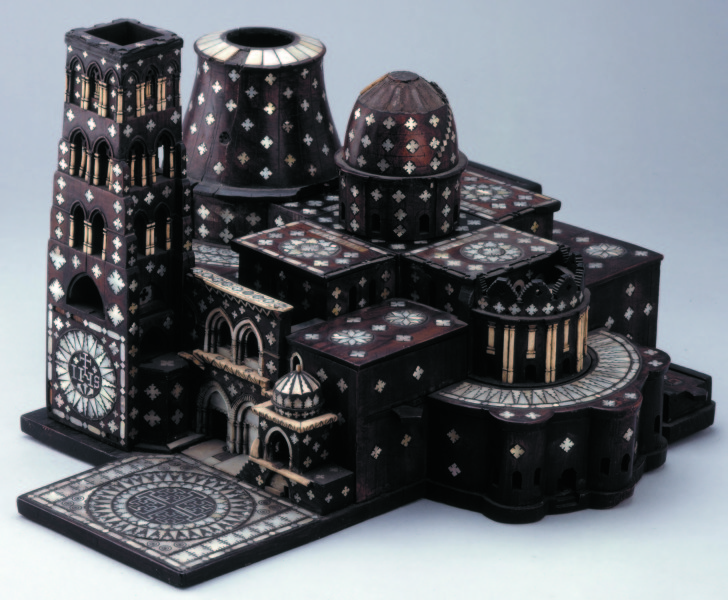

This marvellous exhibition presents religious beliefs in a novel way not through the doctrines but the objects and symbols that people across time have created for a wide range of devotional, superstitious, cultural and ceremonial reasons.

The oldest is the awesome Lion Man a carved figure, half man, half beast, made from the tusk of a woolly mammoth. It is some 40,000 years old and is worn smooth by handling, hence it is assumed to be a devotional object.

The exhibition takes us on a meditative, sometimes funny and often tragic journey through the existential yearning of the human mind: there are shrines and signs, masks and flasks and many a terror with as the Mexican Devil figure.

A poster of a cosmonaut staring into space with the caption ‘There is no God’ (a quote attributed to Yuri Gagarin but possibly a propaganda message) could be compared with the cross made from the boards of a refuge boat wrecked off the Sicilian coast.

Lion Man was discovered in an inner cave in 1939 in fragments but as curator Jill Cook curator says: “We are as much in need here and today of shared story that pieces us together.”

Supported by the Genesis Foundation, Living with Gods is part of a collaboration with the BBC and Penguin Books.

Until April 8th at the British Museum, London, UK

Old Masters Now: Celebrating the Johnson Collection

In the wake of the astonishing £450million auction of Salvator Mundi, now attributed by several – if not all experts – to Leonardo da Vinci, we might suppose that Old Masters will start to compete with the oft ludicrous prices for contemporary works: this indeed was why Christie’s entered the Leonardo itself into their contemporary art auction.

So an exhibition of one of the finest collections of European paintings, including many Old Masters, ever formed in the United States is most timely. Interestingly authentication is one of the key issues dealt with in detail here.

The works were gifted to Philadelphia in 1917 by John Gravel Johnson, a great and wealthy corporate lawyer of the city. The roll call of Renaissance greats is astonishing: works by Botticelli, Bosch, and Titian rub shoulders with those of Rembrandt and Hieronymus Bosch while ‘modern’ masters include Manet and Monet. The visitor will enjoy archive photos of the way in which Johnson lived cheek by jowl (a Renaissance master once hung in the bathroom) with his collection – quite unlike the rigorous environment in which these works are today constrained for their own good.

The discovery of a painted over skeleton in Judith Leyster’s painting The Last Drop removed for aesthetic reasons but now recovered is an example of how modern forensic investigation of paintings recovers extraordinary facts: Johnson, who relied often on his own judgement as an amateur art historian purchased no less than 10 works that he thought were by the hand of Bosch, however examination by experts indicates that only one is unquestionably authentic.

Until February 19th at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, USA

Victorian Passions and Pursuits

My only visit to the extraordinary stately pile that is Blenheim Palace was to see Salon Prive, the annual parade of supercars and vintage classics in the grounds of one of Britain’s most monumental English country houses. The birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill, it is the only non-royal, non Episcopal building in England that revels in the title of palace and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Whether or not you like English Baroque architecture by Sir John Vanbrugh – reviled by some – it has undergone many changes and was saved from ruin by the marriage of the 9TH Duke toA Vanderbilt.

Maintaining such a stately pile has led to some questionable events – a theme park style Chinese light show among them – but the latest exhibition showcasing examples of Victorian art is on safer ground.

Works from the era of J.M.W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood through to Richard Dadd and Aubrey Beardsley are on display. Assembled by Cecil Higgins it shows the range of styles that came about in an era encompassing Aesthetes, Pre-Raphaelites, Decadents and Exquisites as well as formerly unshown botanical watercolours by the 5th Duchess of Marlborough.

Several State Rooms have been given a makeover to look as they would have done during Queen Victoria’s reign. A popular element is a display of the filming of Young Victoria featuring images, costume and a selection of props used in the film.

Until April 16th at Blenheim Palace, Woodstock, Oxford, UK

Pipilotti Rist: Sip my Ocean

Dive into the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney for the most comprehensive exhibition ever stage of the work of one of the world’s foremost video artists. Sip My Ocean covers the spectrum of Pililotti Rist’s work, starting with her early video work of the 1980s and culminating in the large scale immersive installations of today.

The works have been described as an “ode to the big emotions that sustain us as human beings and to the beauty of the world and the universe around us,” and indeed visitors are mesmerised for house by the works.

Born in Switzerland, in 1962 Elisabeth Charlotte Rist, as she was baptised, left home at just 19 and changed her name to Pipilotti, an homage to children’s book character Pippi Longstocking, known for her quirky character and extraordinary strength. From the start, Rist was an innovator, exploring new ways of making art through technology.

Occupying the entire third floor of the Museum, with breakout works in other area, you are invited to sit on oversized red sofas in Das Zimmer; to walk through a magical forest of hanging lights in Pixelwald Motherboard, and a maze of floating fabric in Administrating Eternity. Exhibition curator, Natasha Bullock describes the works of Pipilotti Rist as imaginary worlds that carve a unique vision, with all the attendant depth and weight of painting: ” Rist paints with lights cameras and keyboards.”

Until 18th February at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia

CREDITS

Lion Man Baden-Württemberg, Germany,

40,000 BC

© Museum Ulm, photo: Oleg Kuchar

Judas-devil figure

Mexico, late 20th century

© Trustees of the British Museum

Giovanni di Paolo

Saint Nicholas of Tolentino Saving a Shipwreck, 1457

Tempera and gold on panel

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Callisto Piazza

Musical Group, 1520 Oil on panel

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Judith Leyster

The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier), c. 1639.

Oil on canvas

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Monumental Statue with two heads

Jordan, Ain Ghaznal

ca. 6,500 BC

Plaster

Department of Antiquities Jordan

Lion de Mari-Cha

Andalusia or Southern Italy

11-12th century

Bronze

c. Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pipilotti Rist

Ever Is Over All (still), 1997 Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine © the artist

Pipilotti Rist

Administrating Eternity, 2011

Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

© Pipilotti Rist

Pipilotti Rist

Sip My Ocean 1996 Still from video installation Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine