“Six years ago it changed,” says Venisha Brown. “Christmas will never be the same.”

On Christmas Day 2006, Venisha’s father, music legend James Brown, died of congestive heart failure. At the time some associates were quoted as saying that Brown, the ultimate showman, would have loved the drama of passing away on Christmas Day. In truth, it was probably the worst time he could have gone.

James Brown loved Christmas. In his hometown of Augusta, Georgia, his charitable ventures had made him synonymous with the holiday. For Brown’s family, whose time with him was limited thanks to his busy work schedule, Christmas meant time together. Hours before he was transported to hospital on Christmas Eve, his last telephone conversation with his wife Tomi Rae had been about Christmas preparations. It is hard now for those Brown loved to enjoy the day, which still evokes painful memories.

“It’s a sad time,” Venisha says. “Quiet time, you know? That’s what I did this Christmas: just quiet time. Not to be depressed, not to cry or nothing – but just quiet time and remembering good thoughts. I was actually listening to his music and stuff, just missing him. Anybody who loses a parent, doesn’t matter which day it is, but he just happened to leave on Christmas Day. It’s like… Wow.”

“I’ll be honest with you,” says her sister, Deanna Brown-Thomas. “I think all of us deal with it in our own special way. Peace and quiet for me is the best way to deal with it. I’ve kind of become an introvert on that day for now.”

For the Brown sisters, Christmas comes earlier these days.Since 2007 they have spent the months leading up to the festive period preparing for two annual charity events founded by their father – events they have fought to keep running since his death. Every November they host the annual James Brown Thanksgiving Turkey Giveaway, dishing out hundreds of birds to needy families. Three weeks later they stage their father’s annual Christmas Toy Giveaway.

Gifts at the most recent toy giveaway, which served more than 800 underprivileged kids at Augusta’s James Brown Arena on December 20, included bicycles, dolls, board games and electric keyboards. The day also featured live music, face-painting and a special appearance from Santa Claus.

When their father was alive, he would personally attend the functions.

“The toy giveaways were just awesome,” says friend and producer Derrick Monk. “The kids would get a joy out of seeing that black limo drive up. Yea, they wanted to get the toys, but when Mr Brown showed up on the scene it was a hysterical moment. He would stand out and talk with everybody. He would try to shake everybody’s hand. He was really a people’s person.”

Brown’s tradition of Christmas giving began in the 1960s. He demonstrated his love for the season by releasing a succession of Christmas albums between the mid-1960s and early 70s, despite none of them charting particularly well. It was shortly after the release of the second, 1968’s A Soulful Christmas, that Brown’s first documented Christmas charity event took place; He donated full Christmas dinners to 3,000 needy families in New York.

The following December he performed a six-day residency at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, donating all of the profits to the poor. His Christmas giving continued in 1971, when he delivered food and clothes to an Augusta family who had suffered a house fire. By that point, Brown had begun staging an annual Christmas display at his family home on Walton Way. His ostentatious decorations drew crowds almost as big as his concerts.

“He would have all of these Christmas props,” laughs Deanna. “He would have a big Christmas festival in the yard.It’s funny because now, people still tell me that they remember that. They remember as a young kid going up there.”

Brown would even dress as Father Christmas and entertain local children.

“People now tell me that was the first time they ever saw a black Santa Claus,” she continues. “He would give out candy to the kids and sign autographs and take pictures and there would be carolling there. I remember the cars would be backed down the road trying to get in.”

The annual toy giveaway began in the early 1990s, as an offshoot from the turkey giveaway, which launched in 1990. Nobody is entirely sure where the idea for the giveaways came from, but daughter Deanna thinks it may have been the brainchild of her father’s elderly masseuse, Mr Fuller.

“He and my dad would have very intense conversations,” she says. “He’s passed now. He used to come almost every day when dad was home, to give him a massage. He was an older man and a Christian man and a bible reader and he always talked about how important it was to give to the poor. I know that there was a conversation that they had once and he started it right in 1990.”

Brown’s last ever public appearance was at the 2006 toy giveaway, three days before his death. He appeared at the event despite a persistent cough and shortness of breath, which were diagnosed as pneumonia two days later.

“I remember him coming and getting out of the car and my dad looked so fragile,” says Venisha. “Real thin and he looked sick. But the thing is that giving back and being there for people who are less fortunate meant so much to my father that he just felt that he had to be there. He would put other people’s needs before his.

“After he gave out some gifts he went back home but I said, ‘Daddy, you don’t look well’. His reply was, ‘I don’t feel good sugar, but I gotta be here for my people’. That’s exactly what he said and that was the last time that I saw him.”

Keeping the giveaways going since their father’s death has not been a walk in the park for the Brown sisters. Arguments over their father’s will began on the day of his death. Six years later they remain unresolved and the Brown sisters have had to carry out their father’s charitable ventures every year without any financial assistance from his estate. It has taken ‘concerted effort’, says Deanna. To fund the events they have established the James Brown Family Foundation, whose board members include Reverend Al Sharpton, to raise money through private donations and government grants.

Some changes have had to be made. For instance, a new system has been introduced at the turkey giveaway to stop people abusing their kindness. James Brown, family and friends say, could be too generous for his own good.

“There was a lot of times when I stood in the line there and I would see people come through the line twice,” laughs Derrick Monk. “I would ask him, ‘Hey, didn’t you see them come through the line twice, Mr Brown?’ He would say, ‘Mr Monk, they may have needed two turkeys’.”

“My dad’s pockets were kinda deep,” says Venisha. “If they came and said, ‘Mr Brown, we need a turkey’ – he’s just giving it, you know? But some people see a good thing and they want to take advantage.”

The sisters have solved the problem with the introduction of a computer programme that logs the address of everybody who collects a turkey. If the same address is used twice, the computer alerts the sisters and their fellow volunteers.

“He designed this for people in need, not in want,” says Venisha. “You have some cases that four people will come in line and those four people stay in one household. So now we have one turkey per household and we don’t know if they need it or want it – but that’s not for us to say. And actually, it worked out. We still were able to give back but we’ve seen a big difference in how many turkeys we’ve been giving away.”

The savings have allowed the sisters to spread the love beyond the state boundaries. In recent years they have begun holding more giveaways in Harlem, New York – a community dear to their father’s heart. The New York toy giveaway is held at the Harlem Lanes bowling alley, less than a five-minute walk from the Apollo Theater where James Brown made his name.

The sisters’ plan is to continue launching new giveaways until they run nationwide, but funding for such a project would be extremely hard to come by. They hope for a resolution to legal sparring over their father’s estate in the next year or so, but in the meantime they are focusing on another project: bringing their father’s biggest humanitarian ambition to life.

***

Derrick Monk, who produced much of Brown’s latter day work, believes the singer’s decision to hire him was in itself a humanitarian act. Brown would regularly drive around Augusta checking in on acquaintances and old school pals. He’d knock on the door, chat a little and then give them a wad of cash to see them through whatever hard times might be lurking around the corner. Other times he’d ride around in his black, chauffeur-driven limousine giving fistfuls of hundred dollar bills to kids he passed on the street, telling them to give it to their parents to start a college fund.

Deanna Brown-Thomas says these ‘random acts of kindness’ were a part of life with James Brown: “We’d see him do that all the time. He bought musicians’ houses, cars and sent their kids through school. Bought cars for their mothers. He bought this one lady’s momma a car because hers had broken down and she couldn’t get back and forth to her prison ministry.

“I remember being out in California visiting Venisha. We were in the limousine. He told the driver, ‘Just stop’. He got out the car and started walking across the street – all the bodyguards trying to run behind him, make sure he’s alright – and he’s going over to these homeless people who are on the ground.

“When they look and see it’s James Brown, they rise up like dead people and he just starts giving out money – fifty dollar bills, hundred dollar bills – trying to just talk to them and shake their hands – ‘Go help yourself, brother’, ‘Go do something for yourself’, ‘Go get something to eat and clean yourself up’.”

Brown was on one of his trips around Augusta in 1993, checking in on old acquaintances, when Derrick Monk noticed his famous limousine parked up on Laney Walker Boulevard. Monk had just left his job as a church musician – he cites artistic differences with the preacher – and was driving around town looking for work. Seeing a chance to meet one of his heroes, he pulled over.

“He said to me, ‘How can I help you, young man?” Monk recalls. “I began to tell him, ‘My name is Derrick Monk…’ and when I was telling him my name he started smiling like as if he had heard about me already. He said to me, ‘I heard you can play the hell out of an organ.’ He invited me to his rehearsal at the Imperial Theater a few days later and he hired me. I became his A&R; man at his record label Brownstone Records and started producing songs on him.”

The pair’s first album together, ‘I’m Back’, spawned the single ‘Funk On A Roll’, which hit top 40 in Britain. Their next collaboration was Brown’s fourth Christmas collection, 1999’s ‘The Merry Christmas Album’, whose closing track ‘Don’t Forget The Poor At Christmas’ epitomised his holiday philosophy. But it was their next project that would provide the soundtrack for the Godfather of Soul’s final crusade.

Not long into the new millennium Derrick Monk received a call from Brown, who was staying in an Atlanta hospital for a few days. The singer said he needed to see Monk and to come as soon as possible. When Monk arrived, Brown invited him to take a seat and the pair quietly watched television for a short while.

“Monk,” Brown announced suddenly, “I believe the reason why I had to come to the hospital is because I had to see that they’re killing these kids in school. Come here. They got a piano back here. I want you to hear this song.”

The pair moved to another room where Brown sat down at a piano and pulled a sheet of yellow notepad paper from his pocket, on which he had penned the lyrics to a new track. Plotting out the chords as he went, Brown beatboxed the bass line and sang the lyrics.

Monk recalls: “He said, ‘Son, I want you to go back and write this song and bring it back to me. When I come out I’m gonna record it’.”

Monk never did get to the bottom of what Brown had seen in hospital to inspire the track – or why he had even been in hospital in the first place.

‘Killing Is Out, School Is In’ would become the pair’s most celebrated collaboration. A heavy funk number, it implored young people to resist the allure of gang culture. “Try romance!” Brown cried. “Turn that hat around, take the gun out your pants!”

Brown saw the track as a modern take on his 1966 hit ‘Don’t Be A Dropout’, whose release saw the star work with Vice President Hubert Humphrey to launch a national stay-in-school campaign. Having only been educated to a seventh grade level, Brown travelled around the US on a school tour, talking to kids about the perils of entering adult life without an education. He opened ‘Don’t Be A Dropout’ clubs across the country and on his next tour he donated $500 scholarships to nearby black colleges wherever he stopped. He handed out five scholarships at every show, averaging four shows every week for roughly six months.

Excited by ‘Killing Is Out’, Brown promoted the song vigorously with a succession of press and broadcast interviews, but it got little airplay and failed to chart. It did, however, attract the attention of the National Crime Prevention Council , which was so impressed that it publicly expressed interest in using Brown and the song in TV and radio commercials.

Alongside its pro-school, anti-crime sentiments, the track seemed to be taking a swipe at hip-hop iconography. In an April 2001 interview with Brown, concertlivewire.com suggested that ‘Killing Is Out’ was ‘going against what gangsta rap is all about’. Brown avoided commenting on the genre, instead opting for a more diplomatic response: “Whatever makes your kid go crazy and want to shoot you and shoot his brother, that’s what we’re against.”

But he did give some indication of his thoughts on hip-hop, which ruled the charts at the time. Asked for his take on modern music, he replied, “There is no music, that’s the problem.”

Brown’s relationship with hip-hop was complex. The genre had its roots firmly in the musical template he had created with his funk movement in the 1960s and 70s; the one-and-three beat, the prominent bass and the emphasis on rhythm over melody. Brown remains the most sampled artist of all time, with many of hip-hop’s earliest hits built on looped fragments of his old material.

But while Brown often publicly revelled in his role as the Forefather of Hip-Hop, which fit neatly alongside his various other monikers, he harboured deep reservations about the direction the music was taking. The genre had become famous for its violent imagery. Rap stars frequently hit headlines espousing sexist or homophobic beliefs. In some instances, Brown’s own compositions were the canvases upon which rappers displayed their questionable sentiments.

In 2003, Nelly and Missy Elliott sampled Brown’s yearning, gospel-infused ‘Please Please Please’ on a track called ‘Pump It Up’. In the song, Nelly rapped: “Yea Ma, I heard you like the magic stick, Me I got the gadget stick, It’s like a go-go gadget dick. You know, make her climb the walks and shit… Walk up in the party, girls be swinging they panties, you see they was doing that before I had them Grammies.”

Perhaps most alarmingly, Brown’s groundbreaking, empowering civil rights anthem ‘Say It Loud, I’m Black And I’m Proud’ was sampled by Five Deez on a 2001 track called ‘Got Dough’, which included the lines, “Stank chicks, they sweat my knot and I love ‘em, I got cheese, now to bone ‘em I don’t have to drug ‘em… I love the women, the women love me in return. I bust sperm in the shape of dollar signs.”

Brown’s aspirational tunes, such as ‘Soul Pride’ and ‘I Don’t Want Nobody To Give Me Nothing (Open Up The Door, I’ll Get It Myself)’,hadset out to instil moral values in his young listeners; stay in school, take pride in yourself, work hard, give back to your community. To be so often cited as the inspiration for such divisive music, and to have his own compositions used as the basis for such lyrics, filled him with unease.

“Mr Brown loved hip-hop,” says Derrick Monk. “He was a part of hip-hop. There would be no hip-hop had not there been no James Brown. So he had to love something that he created… But he never felt that music had to be explicit. He thought they could be a little more creative with their lyrics instead of just going to the gutter.”

As time wore on, Brown would become less coy about his thoughts on rappers, choosing to directly challenge them both in his music and in his public statements. In 2005 he recorded two tracks railing against contemporary music. The first, ‘They Don’t Want Music’, was a collaboration with the Black Eyed Peas. The lyrics complained about modern musicians’ reliance on technology instead of musicianship. The second, a demo titled ‘Gutbucket’, was recorded for an album he would die before he could complete. On the track he sang, “Hey rappers, judgement day. We’ve got to save the kids and music is the only way.”

In October 2006, in a press conference at London’s Roundhouse, he bemoaned the dwindling use of horns and pianos. He told reporters about ‘Gutbucket’ and its message to rappers, again urging them to write positive lyrics for their young fans. “We’ve got to put the music back in the music,” he concluded.

A month later at the UK Music Hall of Fame – the last time James Brown would ever appear onstage – he ended his induction speech by saying, “Let’s change our lyrics, clean the music up and take these kids to a better life and a better place.”

Weeks later, at a public memorial service in Augusta, Reverend Al Sharpton recalled his last conversation with his friend and mentor. He said Brown had told him: “What happened to us, that we’re now celebrating being down? What happened that we went from ‘Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud’, to calling each other niggers and hoes and bitches? I sung people up and now they’re singing people down – and we need to change the music’.”

***

Just about everybody James Brown knew had heard his plans to ‘change the music’ on at least one occasion. While running her father’s radio stations, Deanna Brown-Thomas had heard it perhaps more than anyone. The idea had been formulating in his mind for years. What was needed was a drive to get more kids learning the craft musicianship; learning to play instruments and write proper songs. What was needed was a school. A James Brown School.

“Music and education had such a strong place in his heart,” says Deanna. “Having a school was something that he talked about quite a bit. He’d say, ‘These kids ain’t doin’ nothin’ out here. They ain’t playin’ nothin’ ‘cause they don’t know nothin’. They ain’t learnin’ nothin’.’

“When I ran the radio stations for him here and in Atlanta, he didn’t want me dealing with no record companies because he would say, ‘They ain’t playin’ nothin’. The artists that they got, they ain’t doin’ nothin’.

“He was with the Barry Whites, Aretha Franklins. The real heavyweights. Ray Charles. He was like, ‘This is the music. Real instruments. Children, go learn this. Go learn how somebody goes into a studio with a band and not just go in there and put their beats together. Go in there with instruments’. He would talk about how important it was for young artists to learn their music.”

Brown’s ultimate vision, set out in his will, was for much of his fortune to be put into an ‘I Feel Good Trust’ to provide education for needy children, sending them to college on James Brown Scholarships. With Brown’s estate still locked up, the sisters cannot yet go about putting that plan into action – although they say it will be a priority when the legal arguments have been resolved. But they have been able to achieve part of their father’s dream. The James Brown Academy of Musik Pupils (JAMP) opened its doors in summer 2011.

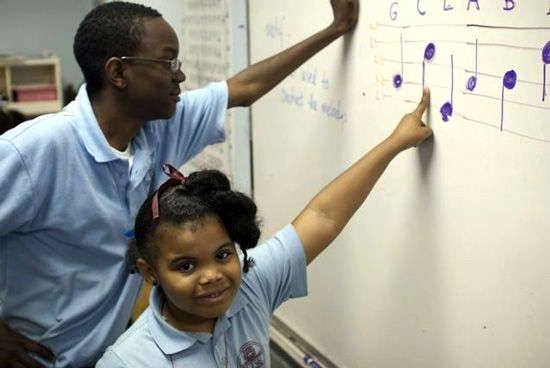

Managed in partnership with existing Augusta music school the C H Terrell Academy, JAMP runs three terms every year and takes in new students every term. Pupils take music history classes, receive instrumental tuition from former James Brown band members and carry out community service, all with a view to eventually creating a college application portfolio that will boost their chances of gaining a scholarship.

Students are split into three groups. Jampers, the least experienced students, are given recorders when they first join and begin learning to read music. When they have a feel for it, they start experimenting with different instruments before choosing a primary and a secondary. They then receive tuition in both.

Jamp Masters, the more experienced musicians, play in a band. They tour around Augusta performing community gigs, which are logged in their college portfolios as community service. At 16, Jamp Masters can become Maestros In Training, working with mentors on their college applications. In just over 18 months, the academy has already helped one Augusta teen to secure a college scholarship.

Fourteen-year-old Neema Colon enrolled in summer 2011, when the academy first opened its doors. A Jamp Master, she used to perform locally as a solo vocalist. Since enrolling, she has become a competent bassist, performing with the Academy band and taking solo vocal spots.

“It’s awesome,” she says. “It’s given me a lot of opportunities to go around and play. I’m not as nervous as I used to be onstage. It changes the way you feel about performing.”

Fellow student Johnathan Mosley adds, “It’s really added a lot of stage presence to my performing and some of the way I play, actually.”

Johnathan, 18, was behind a year in school when he enrolled in the academy’s second term in autumn 2011. He plays drums and keyboards but his instrument of choice is the guitar. When the Brown sisters heard him play, they immediately signed him up on a scholarship. Since enrolling, he practices for five hours every evening after a ten-hour day at school. He was promoted to Maestro In Training level by Christmas 2011 and began work on his college portfolio. His ambition is to become a church musician and he hopes the academy will help secure him a scholarship to train at Hillsong College in Australia.

“I walked into the academy and I really liked the way it was,” he says. “I liked the way they taught things. I used to just play rock stuff. Now it’s changed into a bluesy feel or a jazz feel, something close to that.”

Diversity of music is a key aspect of the children’s studies, says curriculum leader Kimberly Baxter-Lee:“We cover jazz, blues, even a little bit of hip-hop – but how it can be clean, as well.”

A lot of the students have rethought their stances on hip-hop since enrolling, says Deanna: “The music they’re into now, the tastes and the flavour have changed.”

“Oh yea,” laughs Kimberly. “They won’t go to the hip-hop concerts now. They want to know, ‘Do they have a live band?’ They’re at a totally different level compared to how they first came in, which is great to see. They’ve opened themselves up to classical music, country music…”

It’s not just the kids whose tastes have changed.

“These kids have opened me up into the art world like no other,” admits Kimberly. “Before, if it wasn’t classical, I didn’t wanna hear it. Now my ringtone is Mr Brown.”

Growing up in Augusta, Kimberly was accustomed to seeing James Brown around town from a young age. Not realising the level of his fame, she viewed him as a nuisance, always bugging her about her education.

“His favourite words to me were always, ‘How’s school going?’” she laughs. “I was like, ‘Uuugh!’ Every time, it was like, ‘Uhhh, he’s always here!’ Now I’m one of the best James Brown fans you’ve got.”

When Johnathan isn’t studying or practicing his guitar, he can often be found carrying out hours of community service for his college application. He picks up some of those hours by teaching Jampers like Neema. Others are logged when he plays with the band at community events like the turkey and toy giveaways.

“Playing the giveaways has showed me a lot,” says Neema. “There are a lot of people who don’t have what you have and who aren’t blessed like you. Seeing that and seeing how Mr Brown came and gave and spent time there and gave back to the community really inspires you to keep going and keep living his legacy.”

The band is led by former James Brown guitarist Keith Jenkins, who joined the singer’s group in the early 1990s and played with him until his death. Under his tuition, says Deanna, the kids evolved swiftly into a tight, funky band.

“These kids are amazing,” she says. “It’s amazing what they can do with an instrument. Oh my goodness.”

“Keith is teaching these little kids real James Brown riffs, man,” laughs Derrick Monk. “Deanna invited me out to talk to the class one day. I was so impressed. Mr Brown would be so happy. White kids, black kids, Mexican kids – everybody together performing in this one band. It’s funny because you got these little kids playing instruments and singing and doing James Brown songs – and I mean to the tee! It’s just awesome. I think they’re incredible and I know Mr Brown would just be tickled.”

The group can already count at least one legendary artist among their fans. Last year they received a surprise invitation from Prince, who has himself spent the last decade preaching the importance of young people picking up real instruments. He was so impressed by the JAMP band that he invited them to play a pre-show gig for an arena audience at his Chicago residency in September 2012.

“He gave the kids VIP seating at the concert,” says Kimberly. “They sat at round, high-top tables with very chic bar stools, right next to the stairs to go on stage. George Lopez was next to them. Prince had some of them come onstage and dance with him during the show.

“Prince puts on one heck of a show. The kids were speechless. You know it’s an experience that will never be forgotten. He even played Mr Brown’s song, ‘I Don’t Want Nobody To Give Me Nothing’. When we got back the kids were walking around school doing the hand motions to ‘Cool’ by The Time. Too funny!”

The kids have since had their first taste of the recording studio, having made an album of ten tight, funky James Brown covers. Titled ‘Jamp-ism: The New Breed’, profits from the sale of the album will help fund the academy as it continues to take in new students.

Ultimately, the James Brown Family Foundation would like to duplicate JAMP’s success over and over again.

“It would be wonderful to have a JB Academy on every continent,” says Kimberly. “To have it worldwide, since Mr Brown was known worldwide.”

“He always had a vision to help educate,” says Derrick Monk. “He tried to do that with not only his own children but everybody else’s. I mean, look at me. He even educated me, a guy who didn’t have a high school diploma. He was always trying to educate, whether it was school education or just trying to help get someone on their feet. He was always about helping somebody.

“I used to call him the little man with the big heart,” Monk chuckles. “He would laugh every time I’d tell him that.”