It’s quite the cultural leap from anywhere in the UK to rural India, but from the quiet refuge of the quaint county of Devon in the south west of England, perhaps even more so.

Oh, and take a detour via Canada too.

I hadn’t been in touch with Narges Ashtari for a few years, so her having lived in Canada came as news to me. Born and nurtured in her beloved Devon, it seemed an unlikely and incongruous turn of events. Yet as I became reacquainted with Narges and aware of her situation, it quickly became apparent that this unexpected piece of news paled into considerable insignificance compared with the rest of her story.

Narges Kalbasi Ashtari is the middle child of three adopted children. Once the two elder siblings became legal adults, Narges and her brothers embarked on a trip to visit her aunt in Canada. During the holiday, the siblings’ adoptive mother talked to the aunt about her assuming legal responsibility of the younger brother. Narges’ aunt agreed to the proposition, but worried that it was only a realistic scenario if Narges emigrated too, as her brother would simply miss her too much. In a typical act of selflessness, Narges agreed to the arrangement in a heartbeat, immediately opting to sacrifice her secure and successful life in Devon so her younger sibling might have the opportunity for contented family life in Canada.

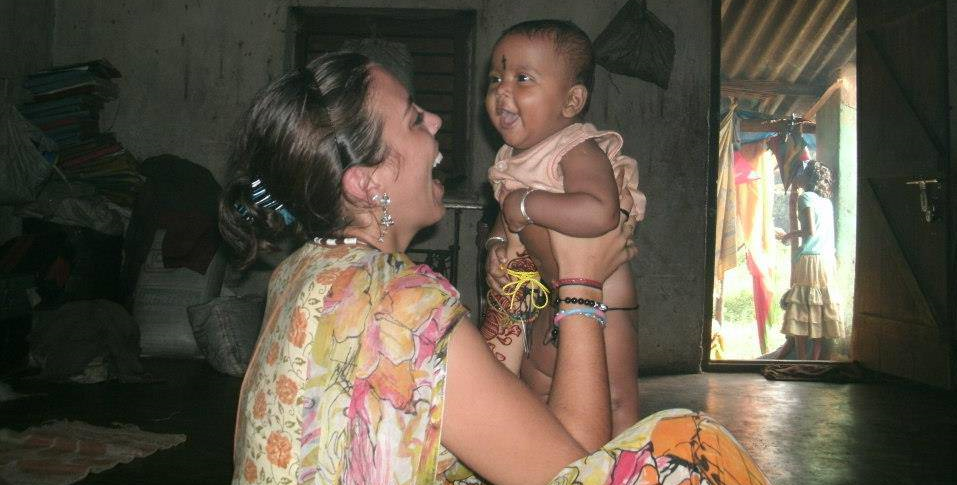

As a consequence of the humanitarian endeavours she initiated whilst living In Vancouver, Narges became known as the ‘Iranian Mother Teresa’. Now… I don’t know about that. Still, with the amount of provocation Narges underwent as friends persisted in teasing her by purposely mispronouncing her name, I can vouch that she certainly possesses a level of patience worthy of the recently beatified icon (it’s a hard ‘G’, in case you were wondering). The Narges I know is compassionate, kind and full of the joy of life. I remember one occasion of her being completely thrilled at the chance to celebrate her adoptive mother on Mother’s Day – as excited as any daughter of their biological mother would be. To a greater extent, perhaps.

As an orphan, Narges has an acute understanding of both loss and gratitude.

However much empathy a person might be blessed with, however much they might weep whilst watching the world’s injustices roll before them on the TV, a true appreciation of the agony some suffer remains elusive to most. Narges is one of the exceptions. People suffering; people in need; people controlled by tyranny. Narges felt wounded witnessing such atrocities inflicted on the innocent, with the pain of it spurring her into action.

Narges’ relocation to Vancouver provided her with the opportunity to start anew. She could have chosen any number of career paths. But she went with vocation, so put in motion her charitable aspirations. She established the Prishnan Foundation, and through her tireless campaigning for the needy in India, achieved extensive support and reputable status. Once Narges had acquired this solid base of trust and bankability, she felt it was time to embark on the next step of her moral adventure.

Upon moving to Rayagada district in Eastern India, as a foreigner with little to her name but a good heart and a good plan, Narges required a donation of two pieces of land upon which to construct her children’s homes. The regional NGO went by the acronym ASSIST. Time would expose this moniker as an absurdity.

Once the buildings had been completed, Narges became aware of the NGO’s change in attitude towards her. She discovered that the land documents she had been provided with were forgeries, and that the land remained under the ownership of ASSIST. Narges made a complaint to the police, but to no avail.

In an interview with the Iranian Mehr News Agency, Narges explained,

“ASSIST thought that once I built the homes, they could somehow get rid of me and then sell them to make money… both of these properties are very expensive and both of them together come to a total of around 80 to 88 thousand dollars. So as you can imagine in a place so poor as Rayagada district, this amount of money is huge and these people would go to any length for money, even if it means killing someone.”

Narges’ case is by no-means a precedent in regard of the extremes of threatening tactics employed by the notoriously-corrupt Indian state authorities. Indeed, the endemicity of the problem is considered to be a significant factor in the failures of the country’s economic growth.

In 2011 Niyamat Ansari, an active advocate for the safeguarding of workers’ rights in the Indian locality of Jerua, was kidnapped by a group of armed men. Ansari, like Narges, had also been involved in highlighting alleged cases of corruption. The kidnappers took Ansari away and brutally beat him for up to one hour. Ansari was later discovered by his family, cold and unconscious. Ansari died shortly after arriving at hospital as a result of the injuries he sustained during the beating.

With the disappearance of a young boy from a community picnic that had been arranged by Narges’ Prishan Foundation, things suddenly turned from sour to sinister. Narges later learned of how the parents of the child had been approached by the NGO. ASSIST instructed the couple to demand money from Narges as compensation for the loss of their son, and how if Narges didn’t comply, they would assist them in taking legal action against her.

Narges refused to pay a penny, having become well aware of the ubiquity of corruption in the district. Besides, the missing boy had attended the picnic under the supervision of his parents and had not been the responsibility of the Prishan Foundation. Narges had reacted to hearing of the boy’s disappearance in the proper way.

“When the child was pronounced missing I had called the police to come and investigate. Two officers showed up an hour and a half later and they did not do a search at all. From that day onwards there has been no proper investigation whatsoever. I have not even been questioned; nobody has ever asked me what happened. From the very beginning the motive was money and still to this day, it remains the same.”

In response to Narges’ refusal to hand over money, the accusations escalated, with the parents of the lost child then starting to make the specific claim that Narges had taken their son and thrown him in the river, just to stand by and watch him drown. The parents’ charge of murder then morphed to one of manslaughter, with the couple making something of a climbdown. They altered their stance of grievance considerably, now claiming instead that the picnic location chosen had been unsafe. Narges’ Indian assistant, Raju Gupta, had also been named as complicit in the alleged crime, but the charges against the local were soon discarded.

No body has been found.

Narges once again approached the police for help.

“I told the police from the very beginning that they were trying to extort money from me but instead of helping me, they were asking me for bribes, too. So from the beginning it’s been absolutely ridiculous and corrupt.”

Last week, Narges was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to one year in jail – in the town where she exposed the corruption, as well as a fine of $4,300. The prosecution’s success in carrying out this miscarriage of justice makes it starkly evident how the local legal system is fetid from root to tip. The authorities in Rayagada District ruthlessly exploit the poverty that they convey to the world, extorting charitable endeavours and shamelessly pocketing the money donated in good faith by well-meaning people.

One of whom, indubitably, is Narges; a woman who leapt out of the trench of passivity and onto the battlefield of international poverty. That’s not a hyperbolic metaphor. Narges has had threats on her life.

“Many times people have tried to harm me. Many times they followed me on the highway trying to crash into my car. In one instance, in the middle of the night, there were police officers outside my home trying to frighten me.”

The present, most pressing detriment to Narges’ life is her imminent incarceration into an Indian jail. Currently on bail, she’s due to be imprisoned this coming Christmas week.

“What is happening to me could have happened to anyone.”

Ominous words that no-one ever expects to hear being uttered by a friend. It’s eye-opening. It’s heart-breaking.

Narges is wrong, though. This particular kind of travesty is reserved for people who care too much; those who open their hearts to help, irregardless of the risks and possible consequences. Call it naivety; call it idealism; call it compassion; call it activism; call it love.

Many of us grow up motivated by the sense that our life’s mission is to somehow make right any perceived injustices we suffered as children. Not many, however, accomplish the putting into practice of these inclinations to the extent that they become renowned for their humanitarianism, as architects of charitable organisations responsible for the construction of orphanages. The children’s homes have been taken from her. They were the essence of her; the physical embodiment of her soul and life’s work.

Narges is now on the other side of need. She is the one that we must help. Narges’ craving to change the world into a better place by improving the lives of the ignored and impoverished makes her situation all the more tragic and difficult to bear,

“I will love and take care of any child who is in need. We should love all children equally, no matter where they are born. A child in need is a human indeed, we should focus on ending poverty globally, and that is what I want to be part of.”

South west England must seem very far away indeed.